By Luke Whyte, Editorial Director

Editorial is open for submissions: https://bit.ly/3aCuaEE

The thing that turned Flash into the definitive tool for web animation in the first decade of the millennium was, it turns out, a suggestion from a journalist at MacUser magazine:

“You should really add a button.”

According to an incredibly well researched article by Richard Moss, the developers of Adobe Flash (or, FutureSplash Animator, as it was known at the time) gave the MacUser journalist a chance to review the product before it shipped.

His button insight then drove the developers to add play, stop, seek and go-to frame buttons, the features that would give Flash it’s capacity for interactivity and set it apart from other animation software.

The rise of Flash

Within a few years of the button epiphany, Flash – with its capacity to embed interactive animation into any web browser and operating system – was quickly becoming the default tool for animating cartoons, games and websites.

In 1998, digital artist Tom Fulp, would create the controversial Tellytubby Fun Land, an interactive Flash game that, much to BBC’s chagrin, featured the Tellytubbies worshipping satan, smoking weed and molesting sheep.

Fulp hosted his game on his new web platform, Newgrounds, which, consequently, soon after exploded into the de facto home for Flash game developers, animators and artists – artists like Homestar Runner:

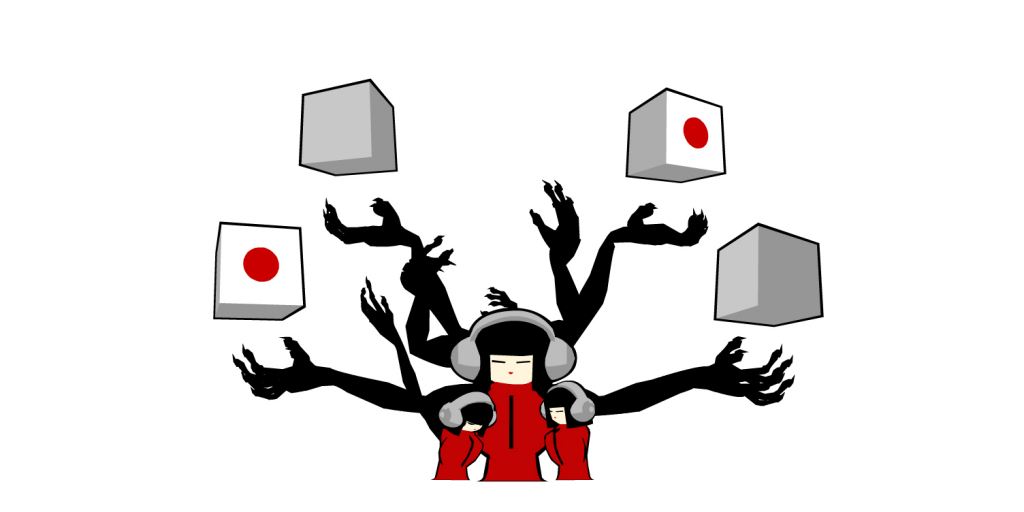

Much of the work produced at the time was fun, silly, sometimes vulgar, but a group of artists saw Flash as an opportunity to push forward the field of digital animation. One such team were Samuel Lanyon Jones and Andrew Cope who, in 2002, released their genre-breaking site, tokyoplastic.

“It was one of those rare sites that gave you an adrenaline rush and a fright too, when you clicked on the loaded graphic and the site literally swallowed you up,” wrote FWA founder, Rob Ford.

tokyoplastic is minting three single edition, fully remastered 4k 60fps artworks from the original site on SuperRare and Lanyon Jones sat down to talk with us about the energy in the Flash animation community at the time and how it parallels the CryptoArt community today.

“When we went online it was before Web 2.0,” Lanyon Jones said. “And it was before all the corporations were spending billions competing for your attention and trying to make things go viral.”

“It was an amazing time. There was the explosion of creativity.”

“There was suddenly this amazing playground where you could go and experiment,” he said. “Two great things: it was a meritocracy and it was egalitarian. You were set free from all the constraints of the art and design industry where there was a well established hierarchy. It was a much more level playing field. If you created something amazing, you’d be recognized for it.”

“It consumed us completely,” Lanyon Jones said of the time he and Cope spent building tokyoplastic. “It was more an experience than a website. It was about a journey that you went on and that’s what we really lent in to.”

The fall of Flash

Eventually, Flash became commonplace and commercialized. The buzz waned. The financial bullies bent many an artist and developer to their Disney-like desires.

Then, in 2010, Steve Jobs wrote his well-publicized letter, Thoughts on Flash, that signaled the start of Flash’s slow, seven year demise in the face of security concerns, a proprietary codebase and the rise of HTML5. At the end of 2017, Adobe cancelled support for the product.

And yet, despite the demise of the medium, Lanyon Jones sees much of the same excitement and creativity of Flash’s early days in today’s CryptoArt community.

“It was exactly like what’s going on with NFTs right now,” he said.

The future that Flash foreshadowed

By putting artists directly in control and contact with collectors, decentralized networks and peer to peer exchange recreate the sense of a community built on meritocracy and egalitarianism that once existed in the Flash community.

The traditional middlemen have been cut out and, as with the Flash community at the time, the old guard is not happy about it.

“When we approached some of those (traditional art) institutions to say, hey, we’re doing this interesting thing, they didn’t get it,” Lanyon Jones said. “They didn’t understand that you could reach millions of people without spending a fortune on advertising.”

It’s an issue familiar to many digital artist in the CryptoArt space today.

“Only now,” he said, the big difference with NFTs is that, “stuff can be monetized.”

A second great parallel between the Flash and CryptoArt communities is that both are in a position to push digital art forward in exciting ways.

“Right now the formats for NFTs are fairly limited,” Lanyon Jones said, “but as the available formats broaden so does the potential for really exciting new art.”

We discussed, per example, Krista Kim’s Mars House, which sold on SuperRare for over half a million dollars, and the evolution of NFT’s into new three dimensional spaces and virtual environments.

(The CryptoArt community) risks what happened with Web 2.0 because there is so much money involved,” Lanyon Jones cautioned. “If institutions get involved then small independent voices will once again get drowned out by commercial interests.”

Nonetheless, there is also a huge opportunity for artists to fight back, to take control of their own work and their own vision.

For his part, Lanyon Jones is excited to bring tokyoplastic back to life and to begin minting new ideas.

“It would be great to make a little money, but that’s not really why I’m here,” he said. “I’m just really excited about what is happening in the NFT space and really excited to be a part of it.”

Luke Whyte is SuperRare's Editorial Director.

So happy to see a vintage Flash work on SuperRare and feel that turn-of-the-century nostalgia! Even though support for Flash has waned, I wonder if it would be possible for creators to include the original SWFs, EXEs, or even better, FLAs (the Flash source file) that were used to create their original works, in the NFT.

Oh wow, thats an interesting idea. It’s at least worth asking some creators what they think.